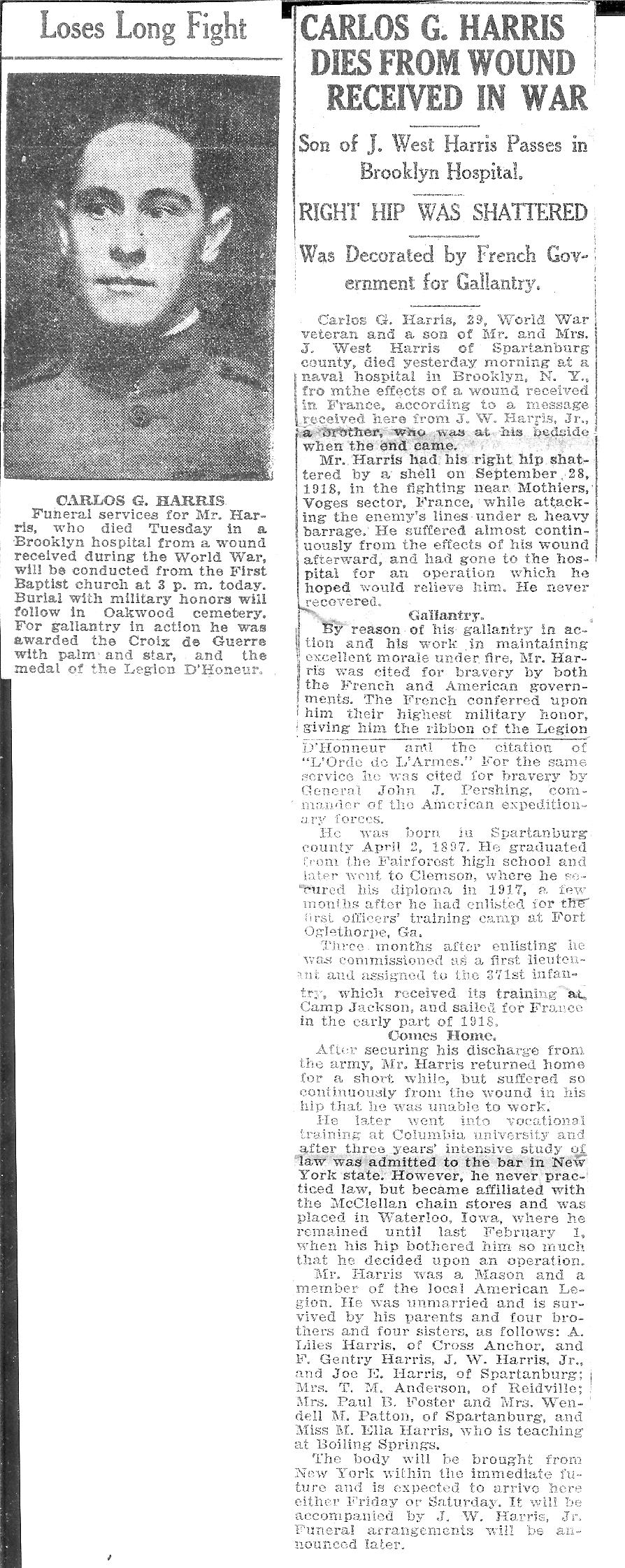

Carlos Golightly Harris

1917

Animal Husbandry

Corporal; Sergeant; Captain; Senior Private; Corresponding Secretary, Literary Critic, President, Declaimer’s Medal ’14; Orator’s Medal ’16; Columbian Literary Society; Secretary, Spartanburg County Club ‘16; Thalian; Secretary, Senior Dancing Club; Basketball ’15, Varsity Basketball ’16, ’17; Captain of the Basketball Team ’17; Assistant Literary Editor of the Chronicle ’15, ’16; Editor in Chief of the Chronicle ‘17.

Spartanburg, South Carolina

Parents: John Weste Harris and Harriet "Hattie" Caroline Gentry

Army, First Lieutenant

C Company, 371st Infantry Regiment, 93rd Division, American Expeditionary Forces

Silver Star Citation (Predecessor to the Silver Star Medal), Purple Heart, World War I Victory Medal, Legion d’Honneur (France,) Croix de Guerre (France)

Apr 2, 1896

Mar 30, 1926

DOW - Died at the U.S. Naval Hospital in Brooklyn, New York of a chronic infection in his femur, which was caused by a cannonball striking it during the Meuse-Argonne Campaign.

West Oakwood Cemetery, Spartanburg, SC

Personal Remembrances

Carlos was the 7th child of 10 children of John Weste Harris and Harriet Caroline “Hattie” Gentry, both of Spartanburg County, SC. Carlos grew up on his family's farm just north of Spartanburg and entered Clemson Agricultural College in 1914, following in his brother Lyle's footsteps.

In his senior year, Carlos was the editor of the Chronicle, a "student literary magazine." I'm also told by Major Brock M. Lusk, a Clemson graduate school history major and former Iraq War soldier who authored a paper for his WWI history class entitled “The Class of 1917 in WWI”, that Carlos organized the senior dance that year of 1917.

Carlos graduated from Clemson in 1917 and went straight into the military via ROTC along with over 100 of his fellow students, being sent first to Ft. Oglethorpe in Georgia. He was made a 1st Lieutenant and in 1918 was sent to France as one of the junior officers of a South Carolina black infantry troop. His troop, the 371st Infantry, was highly successful in the war.

The Negro troops trained in several places including Camp Wadsworth in Spartanburg County, SC for a short time, but there were tensions between the whites and the soldiers in every area they were stationed. In Spartanburg my cousin Edwin said he remembered being told that one day two black soldiers got drunk while in town and were put in jail. Someone went back to the camp and told them that two soldiers were being beaten up, so the troop headed into town on foot to come to their aid. One soldier ran ahead of them and found that the two soldiers were not being beaten, but they were sleeping off the drunk in the jail. He hurried back to meet the angry troop and told them, stopping what might have become a riot. The troop turned around and went back to the camp. They were subsequently moved out of the area, no doubt to reduce tensions in this racially segregated area of the South where the Confederacy was still being celebrated. A recent BBC News article on a new novel about the 369th Infantry said they were moved around to different training areas in the South and everywhere they went they were spat on and beaten up, but they had great restraint; they never met violence with violence even though they were trained to fight. They were sent to the front too soon where, despite their having less training than the white troops, they earned a reputation as a fierce fighting regiment.

Carlos was a junior officer with the 371st Infantry. On the day he was severely injured, 28 Sept 1918, his commanding officer came down sick and he placed Carlos in charge of the coming battle. My cousin Edwin said he was told by a fellow officer and friend of Carlos' that everyone in the troop believed the commanding officer was actually sick from fear. Carlos' troop stormed a hill where the Germans were waiting. Unbeknownst to them, the German officer had told his men to shoot over the American's heads until they reached a predetermined line, then shoot to kill. Many of the regiment were injured. This greatly angered the troops, and when next they attacked, they took out their anger on the enemy and showed no mercy. They killed all the Germans, even those who surrendered. During the battle, Carlos was hit with a cannonball in the hip. The friend, who was an officer in the same troop, was nearby and said he saw Carlos thrown high into the air and somersaulted. At the time he did not believe anyone could survive such a direct hit.

This may explain why no one brought him medical aid. Carlos told his family how he woke up naked on the quiet battlefield, since while he was unconscious, scavengers had stolen all his possessions. An ambulance driver eventually came around picking up bodies. Carlos was put on a cot in the ambulance underneath a blanket.

There are 2 accounts of what happened on the drive into Paris. The more dramatic account says Carlos was put underneath another man whose blood was dripping on Carlos’ face. On the way to the city, the driver stopped at a tavern and went inside, and didn't come back. Carlos was cold and hurting and, with blood dripping in his face, he got mad. He reached up to the man above him who was still dressed, took his pistol out of its holster, wrapped his blanket around his body and hobbled inside the tavern. He found the French driver drinking and when he didn't want to leave, Carlos put the gun to his head and said, with a few choice words, he'd better get him to the hospital or his own brains would be splattered on the bar. The French driver understood, quickly got back in the ambulance and drove to the hospital at breakneck pace.

In the second less dramatic account, Carlos was the one on the top bunk and the injured man on the bottom bunk asked Carlos to move because Carlos’ blood was dripping in his face. Carlos could not move, however, and neither could the other man. On the long drive Carlos asked the driver several times to get him something to drink. Eventually the driver stopped at a tavern and brought Carlos some unpleasant alcoholic beverage. By the time they got to Paris, the man in the lower bunk was dead.

In the Paris hospital during triage, Carlos was very lucky. He was treated by the best orthopedic surgeon in France and perhaps the best in Europe.

Carlos was listed as "Missing in Action" for a month. When his family next heard, Carlos was in the Paris hospital with his hip shattered into 5 pieces and lung damage from mustard gas. He was eventually transferred to the Naval hospital in New York and given a titanium hip. His sister Mella wrote that when he returned home, she was so glad to have her older brother back, and proud to be seen with Carlos walking down the street in his uniform and cane.

Carlos eventually studied law in New York at Columbia University for three years along with his brother John and passed the NY bar exam in 1925. However as time went on he wrote that he was uninspired by each type of law he could have chosen to practice. When he was offered a job to became a store manager for the McClellan Department Store chain, he took it. They sent him to Davenport, Iowa as the store manager and he corresponded regularly with his family. His sister Mella kept all of his letters to her and some that he wrote to other family members. I wonder now if Carlos went so far away from home just a year before he died because he realized there was no hope for him and he wanted to spare his family watching him deteriorate.

I asked Mella if Carlos ever married and she said no. She said Carlos had fallen in love with a nurse in NY, but he decided not to marry her because of his deteriorating health. He did not believe he could provide for a wife and children. In one of his last letters, he mentioned a former girlfriend in his hometown but I think he was answering a question Mella asked him. Carlos' letters to his mother and sister were full of chatty talk and asking about beloved relatives, but in his letters to his father he was more blunt about his injuries. In one letter from 13 Feb 1922, the doctor at the military hospital had persuaded him to get a new x-ray which showed chronic infection eating away the inside of the bone. The doctor wanted the bone to be "broken open and go in and burn out the bone in the hip and down the femur," but as far as I know Carlos did not let him. They had no antibiotics then, only opium and morphine for pain.

Carlos never recovered from the injuries he received on that battlefield. He walked with a cane and was in constant pain. Mella also said his lungs did not recover completely from the mustard gas. The operation the doctor advised may have prolonged his life but he waited too late. When he finally returned to the New York Naval hospital in February 1926, he was weak from the infection having spread throughout his body and he died from septicemia with his brother John beside him. His mother Hattie later received a war pension.

According to his nephew Edwin Foster, so many people attended Carlos' funeral at the First Baptist Church in Spartanburg that the Main Street had to be cordoned off by the police.

Jeni Reinhart

Niece

July 2014

Additional Information

Silver Star Citation

General Orders: GHQ, American Expeditionary Forces, Citation Orders No. 2 (June 3, 1919).

By direction of the President, under the provisions of the act of Congress approved July 9, 1918 (Bul. No. 43, W.D., 1918), First Lieutenant (Infantry) Carlos G. Harris, United States Army, is cited by the Commanding General, American Expeditionary Forces, for gallantry in action and a silver star may be placed upon the ribbon of the Victory Medals awarded him. First Lieutenant Harris distinguished himself by gallantry in action while serving with Company C, 371st Infantry Regiment, 93d Division, American Expeditionary Forces, in action on Hill 188, on 28 September 1918, Vosges Sector, France, and by his brilliant leadership.

LT Harris’ Taps inscription reads as follows: By his own inclination, the “Duke of England” landed in Clemson in the fall of 1913; and as the poet would phrase it, “Ad astra per aspera,” so has it been with Carlos. “C.G.” hails from the grand old “City of Success,” where the sun shines brightest and where the girls grow sweetest. But this fact does not establish for him a home, when Atlanta holds within its mystic realm one heart that beats for another. Among the courses, “C.G.” chose that one best suited for his disposition – dealing with livestock. Carlos’s loyalty to his Alma Mater is strongly manifested by his college activities, being a hearty supporter of everything that is elevating to both him and his fellow-students. “C.G.’s” congeniality and the fearlessness with which he has discharged his duty, have won for him many staunch and intimate friends.

LT Harris as the editor in chief of the Chronicle wrote the following editorial in the February 1917 issue:

OUR NATION’S COURSE

“What will the United States do?” is the question of the day; and the question that puzzles not only the common people but the greatest minds of America as to which is the best way to answer it. There seems to be two great motives effecting the minds of the people of the United States. The first is, to avoid war at any price; which motive seems to me to be either the outgrowth of a false and erroneous imagination of honor and credit, or the manifestation of the weakest and lowest principles one would imagine – that of utter selfishness, that motive which prompts us, as a nation, to uphold our honor and prestige for which we have so often fought and bled to obtain. Which would be the more honorable, to enter the war as the deciding factor of bringing about worldwide peace, and uphold our nation’s rights, or sit by with weakness and patience, and afterwards suffer the loss of our prestige, and hear the character of our nation ridiculed with indifference by all the world? Has the world to-day a single eye to our advantage? The talents and rights which Heaven has bestowed upon this nation are no less virtuous than those bestowed upon any other nation.

But to say the United States is desirous of war is to commit a vulgar error. She has already taken more than any other nation of her size and strength would have done. We have, however, reached the point where “sacrifice ceases to be a virtue,” and we intend to defend our rights without prejudice influencing our action one way or the other. We can’t any longer give as a sane reason for tolerating the unjust actions of any other nation, that we are tenderly considering our future generations. Further reasoning thus would amount to the same as saying: “We will sacrifice our honor and rights to stay out of war so that our children may be benefited.” Would giving up all that makes and maintains a great nation benefit our children, or would it make more obedient drudges of them? We do not want war, but war seems to be the alternative we now have left us. But whatever is done let it be done with consideration so that the United States shall reserve her seat among the great nations of the world.

Frank Roberts, on pages 134 thru 138 in his book “The American Foreign Legion: Black Soldiers of the 93rd in World War I” describes in detail the ambush and battle in which LT Harris was wounded. This book can be found in Clemson’s Cooper Library.