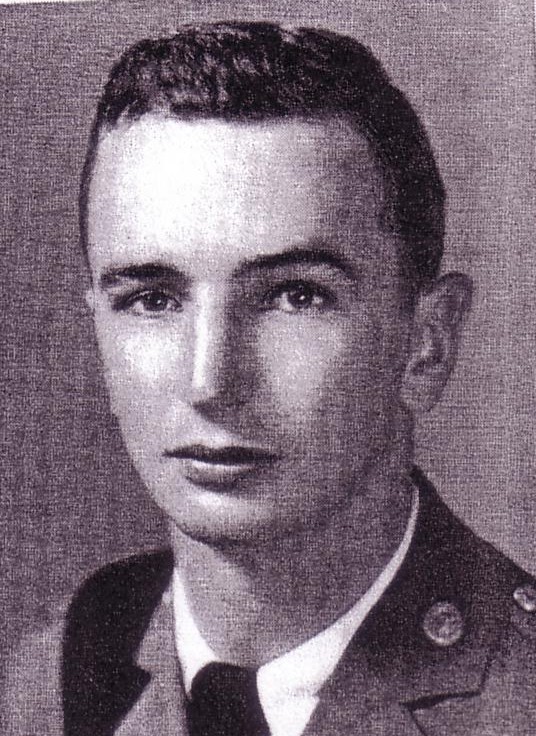

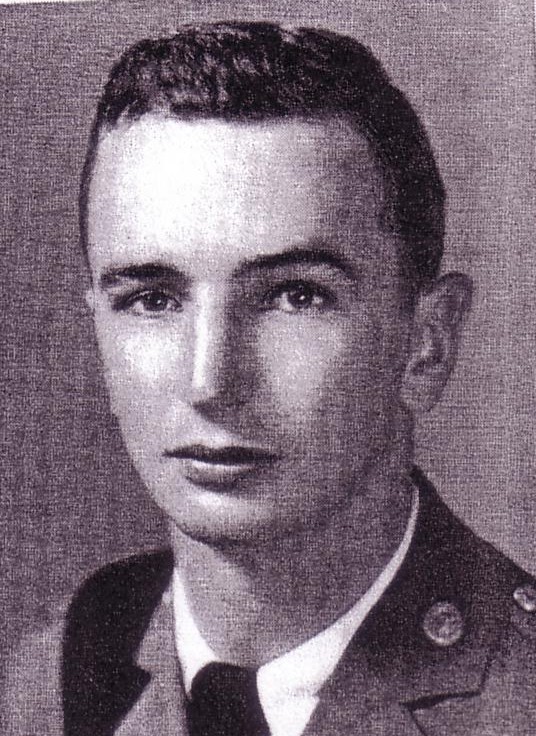

John Ellison Muldrow, Jr

1937

Civil Engineering

Corporal, Sergeant. First Lieutenant, Kamp Klark Clan, President A.S.C.E.

Bishopville, South Carolina

Married, Betty Simpson Muldrow; no children

Navy, Lieutenant Commander

Commanding Officer, Navy Patrol Bombing Squadron 108 (VPB-108)

Navy Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart, Air Medal with Four Gold Stars, American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, World War II Victory Medal.

Sep 14, 1916

May 9, 1945

Killed in Action - Lt Cmdr Muldrow and his PB4Y-2 Privateer Patrol Bomber crew were lost when his aircraft crashed into the sea as a result of battle damage received during a low-level bombing and strafing attack on Japanese installations on Marcus Island in the Central Pacific, east of Iwo Jima.

Lt Cmdr Muldrow’s body was not recovered. His name is inscribed on the Courts of the Missing at the Honolulu Memorial, Honolulu, Oahu, Hawaii. A memorial marker honoring Lt Cmdr Muldrow was placed by his family in the Bishopville Presbyterian Cemetery in Bishopville, SC

SE

Personal Remembrances

The tribute below was received in February 2013 from Dennis Scranton of Miles City, Montana. Mr Scranton was a US Navy Aviation Radio Technician First Class and the radio/radarman on Lt Cmdr Muldrow’s PB4Y-2 Privateer crew from the fall of 1944 to May 1945. Mr Scranton also provided the photos in the profile, with the exception of the TAPS photo. He is the second person from the right in the front row of the crew photo and Lt Cmdr Muldrow is in the center of the back row. Mr Scranton has written a book, titled Crew One, A World War II Memoir of VPB-108, Merriam Press, 2001, describing his experiences during training and combat action in the Pacific. He dedicated the book to Lt Cmdr John Ellison Muldrow.

“That is a fine thing that you are doing there at Clemson, and thank you. I was a crew member of John Muldrow's crew, otherwise known as Crew One. This was John's second tour of duty in the Pacific where he had previously flown PB4Y-1 aircraft or nearly an exact duplicate of the AF B-24. On his second tour we were flying PB4Y-2 aircraft that were much larger with much more firepower. I did write a book that was dedicated to John Muldrow and contains details of the raid on which he was killed if you should desire more information about that fateful day. The book is available on Amazon under the name Crew One by Dennis Scranton.

There were two tours of duty. When you read my book, it will be clear to you that, during the first tour, a crew was shot up by an Emily (a large Japanese flying boat) and the pilot wounded. He was replaced by John who due to his rank date entitled him to the title of Executive Officer. After the tour was completed the then CO (Eddie Renfro) was reassigned and John became CO of the new squadron being formed.

VB-108 was the first tour. VPB-108 was the second tour with the P referring to Patrol Bombing squadron. When it was activated again in 1944, a commissioning ceremony was held once again. My memory is a bit foggy on that part. I refer you to my book as there is a squadron history there....ships sunk, bombing raids, planes shot down, number of missions etc. I believe it was early, or possibly at the end, where I stated that Crew One would follow anywhere John Muldrow led. He had that certain something all great leaders have and we sensed it. He was a great man, a brilliant man, but perhaps a bit foolhardy at times. Flying without his own crew is a superstition of bad luck shared by all flyers. The only time he did, it was fatal.

There was an ongoing unfriendly rivalry between the exec and John. Competition was fierce between the two. Until John's death we were ahead in ships sunk and raids in general. Keep in mind our bombing was at 25 feet and if two planes, the second came in at 75 feet as was the case on Marcus Island. John hit the island at 25 feet. It was a small island and gunned like an aircraft carrier. The flak was unbelievable. My book tells the story of why the raid was so important. If not for the reasons set forth, no one would have ever attacked the island. Many mistakes were made that day, May 9, 1945, Mother's Day. I am not a well trained writer. I wrote the book the way it happened and tried to give the reader an impression of how it was from an enlisted man’s standpoint. We were clearly warned that flying with John, we would not likely come home. We would have fought for the privilege to stay in his crew. It was an honor to fly with him. A brother of a good friend died yesterday at 94. He was in the AAF flying B 26s in the Pacific. Badly shot up, he saved his plane and crew by flying directly over the flight deck of an enemy carrier at extreme low level knowing that their guns all pointed out. John was every bit as daring and resourceful. There are many stories of such events.

I am really pleased you are honoring John. My goal in writing the book was to immortalize John Muldrow. What you are doing is more of the same. I am pleased to be able to help you through our common goal. Thank you for allowing me to assist you. Delighted to be a part of the endeavor.”

The following tribute was provided in February 2013 by Albert A. Malouf, San Mateo, CA. Ensign Malouf was co-pilot and navigator from October 1944 to May 1945 on Lt Cmdr Muldrow’s PB4Y-2 Privateer crew, “Crew One,” during Lt Cmdr Muldrow’s second tour of duty in the Central Pacific.

“I was co-pilot and navigator to the skipper, Lt. Cmdr. John Muldrow. During the first week of October, 1944, VPB 108 was formed and I met Lt. Commander John Muldrow, our squadron commander, and the members of crew one. I felt very lucky and privileged to be flying as a copilot with the “skipper”.

Lt. Cmdr. John Muldrow was friendly and spoke softly. I sensed that he was confident in himself and his ability to lead the squadron. He was not intimidating and showed respect to those under his command. I wanted to give him my best effort and I knew he expected nothing less. The crew, who eventually let all the other crews know that they were “Crew One,” also bonded to the skipper and excelled in the performance of their duties. On October 11th we flew a B-24 to Alameda Naval Air Station and then to NAS Crow’s Landing, California near Modesto.

It was at Crow’s Landing that we received the PB4Y-2 aircraft. Crow’s Landing was a small one strip airfield in the central valley that had farms and livestock ranches around it. My log book shows we flew seven days in October, mostly after the 20th of the month, probably because the new planes were slow in arriving. We practiced bounce landings (landing and taking off), emergency procedures and instrument ground controlled approaches. At the end of October Lt. Comdr. Muldrow signed my log book showing I had 431.6 hours of flying time.

I bid my family farewell on New Year’s Day, 1945. I knew we would be flying to Hawaii soon. On January 18th we prepared to fly to Fairfield about 50 miles north of San Francisco. Fairfield was later called Travis Airfield. We were last to takeoff because we were waiting for the skipper who I knew was saying goodbye to his wife Betty. I think I looked out the window and saw them together, but 65 years is a long time and keeping the facts and the imagination from mixing together can be difficult. The crew members that we did not need for the 2,200 mile flight to Hawaii were sent by ship. Two large gasoline tanks were put into the bomb bays. On January 19th, around 2 or 3:00 o’clock in the morning, we took off for Hawaii. Guess who navigated for the squadron? As we flew over the Golden Gate Bridge, I looked down and could almost see my home since the city was no longer being blacked-out. I wondered if I would ever see it again.

In early May, 1945, all Privateer Squadrons on Tinian were on a one hour alert to attack Marcus Island which is about 400 miles NE of Tinian. On May 8th Crew One was on standby and no strike was called. On May 9th a strike against Marcus Island was called and half of squadron VPB-102 and half of squadron VPB-108 were ordered to attack Marcus at dawn. Lt. Comdr. Muldrow’s crew was not on standby that morning, but he always said he would lead the attack. He didn’t wake up his crew but took Lt. Wallace’s crew who were on standby and ready to go. VPB-102 attacked minutes before the skipper attacked. A plane from VPB 102 was shot down with no survivors.

Lt. Comdr. Muldrow was then shot down. There were five survivors including Lt. Wallace. A submarine picked up the survivors under fire and at great risk of being hit by the shore batteries on Marcus. Two Japanese planes on Marcus were destroyed. As always you ask yourself “was it worth it.” Supposedly the attack was to protect the fleet and supplies that were at Ulithi.

On the morning of May 9th I was walking to the mess hall for breakfast when a fellow officer asked me if I had heard the news. When he told me the skipper was shot down I was devastated. I can’t put into words how I felt. I was then told that two planes were sent out to look for survivors. Soon after that we heard that a submarine picked up five survivors but the skipper wasn’t one of them. I thought of Betty, just as I thought of all the mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters, as I walked among the 6,800 crosses on Iwo Jima. Reading about it and seeing it do not have the same effect on your deep inner feelings.

All those who flew with Lt Commander Muldrow had great respect and admiration for him. The skipper deserved receiving the Navy Cross, his many Air Medals, and the loyalty and admiration of all the men who flew under his command. He was a brave and skilled pilot who performed his duties to the highest standards of the United States Navy. He deserves having his name on the Clemson University Scroll of Honor Memorial and I thank you for all that you are doing for the Muldrow family. I have a good feeling knowing that he will be remembered for many years to come. Not a May goes by that I don't think about Lt. Cmdr. Muldrow, a great skipper and leader.”

The following, along with the citations for The Navy Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Air Medal and several newspaper articles, was received from Jim J. Muldrow, Wilsonville, Oregon in January 2013. Jim Muldrow was a first cousin of Lt Cmdr John Muldrow.

“Thank you for your conscientious efforts in updating profiles of cousins John E. and Henry G. Muldrow in the Clemson University Memorial. Their deaths were a tragedy not only in their untimely deaths, but also the fact that they were the only sons in their respective families.

John Muldrow's mother was a widow at the time, and he and his wife had no children. His wife, Betty Simpson, later remarried and we have lost track of her. Henry G. Muldrow was married and had a daughter named Mary Virginia as you have indicated. Mary Virginia was born while Henry Muldrow was overseas and he never had the privilege of meeting or knowing her. Mary Virginia is also deceased as you have indicated. My father left South Carolina at an early age and settled in New Mexico so our branch of the family is not too well acquainted with the South Carolina family. However, I named my oldest son after Lt Commander John Muldrow because I felt that his heroism in action should not be forgotten and perhaps would serve as an inspiration to the family.

I am the youngest of three surviving first cousins, but I am 85. The material sent to you on the Squadron was found by my older brother, very accidentally, on a trip to South Carolina and then passed on to me. Your generous efforts in updating John Muldrow's profile in the Clemson Memorial will preserve his memory for future generations of our family. Once again I extend the appreciation of the Muldrow family for your most generous participation and support in the Clemson Memorial Project.”

The following undated comment was written by Lt Leo G. Wetherill, USNR (Ret), co-pilot on Lt Cmdr Muldrow’s PB4Y-1 Liberator bomber during a mission on 11 April 1944 and is posted on the website www.ww2pacific.com/stories.html.

“Sinking of the I-174: It has now been confirmed by the Navy Dept. that the Japanese submarine I-174 was sunk 12 April 1944 by Lt. John Muldrow and crew flying a PB4Y-1 Liberator. I was the co-pilot. We were attached to Bomber Squadron VB-108, flying out of Eniwetok. The attack took place at Lat.10 min. 45 degrees N., Long. 152 min. 29 degrees E. On 29 Apr 44 RO-45 was sunk by Montgomery (CVL-26) task group, MacDonough (DD 315) and Stephen Potter (DD-538). They were originally credited with sinking the I-174, but a postwar examination of records indicates that it was the RO-45 that they sunk, crediting us with sinking the I-174, since she failed to answer when called on 11 Apr 44.”

Note by Dave Lyle - John Ellison Muldrow, Jr. and Henry Green Muldrow, Jr. were first cousins.

Additional Information

The Secretary of the Navy Washington The President of the United States takes pride in presenting the Navy Cross posthumously to Lieutenant Commander John Ellison Muldrow United States NavyFor services as set forth in the following citation:

“For extraordinary heroism as Flight Leader and Pilot of a Navy patrol bomber, attached to Patrol Bombing Squadron One Hundred Eight, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Marcus Island in the Pacific War Area, May 9, 1945. Piloting the first plane to take off on this extremely hazardous daylight raid, Lieutenant Commander Muldrow unhesitatingly risked his life to lead his flight at perilously low level over heavily defended enemy territory and, although Japanese antiaircraft fire disabled one engine as he entered the target area, boldly defied the rapidly increasing volume of bursting shrapnel and accurate small arms fire to continue his approach. Undaunted when the merciless barrage sheared the other engine from the wing and set the interior of the bomber ablaze, he held an undeviating course, cutting through the blasting fury of powerful Japanese gunfire and flying his plane with great skill and judgement despite the powerful opposition until his fatally damaged aircraft, with the entire crew on board, crashed into the sea during withdrawal from the target. A superb airman, Lieutenant Commander Muldrow, by his daring combat tactics and resolute disregard of all personal danger, had completed his assigned mission in the face of overwhelming odds and contributed essentially to the infliction of heavy casualties on enemy troops, the destruction of two hostile aircraft and the intensive damaging of vital Japanese installations during this fierce strike. His unwavering devotion to duty upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Services. He gallantly gave his life in the service of his country.”

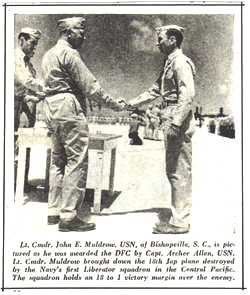

For the President James Forrestal Secretary of the NavyCitation to accompany the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross to Lieutenant Commander John Ellison Muldrow, United States Navy. For extraordinary achievement in the line of his profession as Patrol Plane Commander of a PB4Y airplane, Bombing Squadron One Hundred Eight, during the operations of the U.S. Naval Forces against the Marshall-Gilbert Islands on 26 January 1944. While on a long-range search and reconnaissance flight, an enemy convoy was sighted east of Eniwetok Atoll. In the face of heavy anti-aircraft fire he conducted a daringly skillful strafing and bombing attack at mast-head level sinking the cargo vessel with two well-placed bombs and returning to sink an escort vessel with machine gun fire. Following which, he continued and completed safely the tiring but vital patrol mission. His conduct throughout was in keeping with the highest traditions of the naval service.

Citation to accompany the award of the Air Medal to Lieutenant Commander John Ellison Muldrow, United States Navy: “For meritorious achievement in the line of his profession as Patrol Plane Commander of a PB4Y airplane, Bombing Squadron One Hundred Eight, during the operations of United States Naval Forces against the Marshall and Gilbert Islands. On 18 February 1944, he participated in a low-level attack on shipping in Lele Harbor, adjoining the enemy base at Kusaie Island, scoring a direct bomb hit which contributed to the sinking of a coastal cargo vessel. On 23 February 1944, he carried out an extremely difficult mission, a low level attack on a coastal cargo vessel sheltered in Lele Harbor by hills which rose abruptly from the shore where the vessel was moored. In the face of accurate enemy anti-aircraft fire which riddled his plane, he made five successive bombing runs which so severely damaged the vessel that it was immobilized. On both of these missions, shore installations were heavily strafed. The accomplishment of these vital blows at the enemy’s sole source of supply under the especially hazardous conditions faced was a deed of great intrepidity, high courage, exceptional airmanship, and in keeping with the highest traditions of the naval service.”

After serving as the Base Operating Quartermaster at the Naval Air Station, Coco Solo, Panama Canal Zone and as an instructor at Jacksonville and Lake City, Florida, Lieutenant Commander Muldrow was assigned in January 1944 to the Pacific as Executive Officer of Navy Bombing Squadron 108 (VB-108) at Nuku Fetau, Ellice Islands flying a PB4Y-1 Liberator bomber (Navy B-24 variant). He remained with VB-108 for the remainder of the squadron’s deployment in the central Pacific, with stationing at Apanama, Gilbert Islands and Eniwetok, earning a Distinguished Flying Cross and three Air Medals for his combat actions. Lt Cmdr Muldrow assumed command of the squadron upon its return to California in September 1944. The squadron was reformed at Naval Air Station Alameda, CA and began training for its return to the Pacific. He moved the squadron to NAS Kaneohe, HI in January 1945 after it was re-designated Patrol Bombing Squadron 108 (VPB-108) and equipped with the new PB4Y-2 Privateer aircraft. From there the squadron deployed for combat operations to Peleliu, Tinian, and Iwo Jima. Lt Cmdr Muldrow was flying out of Tinian on May 9, 1945 when he led an attack on Japanese air and shore assets on Marcus Island. He and seven members of his crew were killed when his aircraft was severely damaged by Japanese shore batteries on Marcus Island and crashed into the sea. Five members of his crew were rescued by a submarine, the USS Jallao. For his service during his second tour in the Pacific and his actions on May 9, 1945, Lt Cmdr Muldrow was awarded the Navy Cross, the Purple Heart, and two additional Air Medals.

The following article was printed in the Lee County Messenger, Bishopville, SC sometime during the latter half of 1944 between Lt Cmdr Muldrow’s first and second tour in the Pacific. It was provided in January 2013 by Jim J. Muldrow of Wilsonville, OR, a first cousin of Lt Cmdr John E. Muldrow.

Lt Comdr Muldrow Saves Task Force From Detection

A new Liberator search plane which played the role of a fighter helped a large American task force escape detection in the battle for the Marianas. Piloting “Hell’s Belle,” his Fleet Air Wing Two Liberator, on a routine search patrol far out over the Pacific Ocean, Lieutenant Commander John E. Muldrow, U. S. N., of Bishopville, South Carolina, passed a friendly task force steaming towards Saipan, less than 200 miles away. Six Grumman Avengers, the Navy’s deadly torpedo planes, darted from one of the carriers to investigate the four engine stranger.

“They flew alongside,” Lieutenant Commander Muldrow recalls, “had a good look at us. They stayed with us for about 10 minutes as we took a course ahead of the task force and towards Saipan. After the TBF’s left us we were cruising along 1,500 feet above the water when Pollard, my port waist gunner (Donald I. Pollard, Aviation Machinist’s Mate, Second Class, U.S.N.R., of 3506 Missouri Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri) sighted a twin engine plane about 10 miles away. It was coming towards us and slightly across our course. Beautifully streamlined, it was sleek and black, with gray under the wings, Red discs outlined in white told us it was an enemy plane—we recognized it as a Jap twin engine fighter plane”

The Liberator’s regular job is to fly search patrols deep into enemy territory, discover and report on all enemy ships and planes. It is not supposed to attack enemy fighters. Still, the Japanese was on a collision course with the task force. Detection of the force was inevitable. Lieutenant Commander Muldrow acted without hesitation. “We applied full military power,” he said, “nosed the plane down where we were less likely to be seen by the Jap, circled to the left and started climbing so as to bring us up on the fighter’s tail. We came out of the turn just below the Jap and about 1,200 feet distant.

“My bow, top turret gunners, and my port waist gunner, opened up at this range. We couldn’t afford to miss. The Jap plane was faster than our Liberator. My bows again proved to me that they are the best gunners in the air. The first tracers tore into the starboard engine and fuselage. Meanwhile, the Jap was returning the fire from twin guns in the turret aft of his cockpit. The Jap’s starboard engine and wing flared. We then concentrated on the port engine and it soon started to burn. The Jap went into a steep dive, not out of control, however. It was apparent that he was trying for a water landing. He hit the water with such force though that the fuselage tore off from the wings, broke up and sank at once. Still floating on the water were the wings, also part of the tail. When we went to look there were no survivors.”

In six months Lieutenant Commander Muldrow saw more stirring action in the Central Pacific combat zone than he thought possible. On January 4, 1944, he took off from San Francisco in response to an urgent call from a Liberator squadron in the Central Pacific for a replacement pilot. Late in the afternoon of January 7, he looked down from the cockpit of a Liberator search plane at death and destruction less than a hundred feet below on the parched surface of a coral atoll in the Marshall Islands. Two multi-engined Jap seaplanes, an oiler and a patrol boat were sinking in the harbor. A dense cloud of smoke arose from flaming hangars, radio installations, barracks and other buildings. Eight Liberator search planes, skimming low over the water from their base almost astride the Equator, had just surprised the strongly defended Jap base at Wotje Atoll with another of their spectacular attacks at tree top level.

Shortly after this indoctrination in combat Lieutenant Commander Muldrow was about 40 miles from enemy held Eniwetok on his first search patrol when he sighted through the haze a large Jap tanker escorted by two patrol boats similar to the American destroyer escorts. Within 60 seconds he swept across the tanker just high enough to clear the masts and dropped two bombs. “I could see the ship’s propeller spinning,” Lieutenant Commander Muldrow said, “as the explosions lifted the whole stern out of the water. We did a wing over and crossed back over the ship and the two escorts, with the gunners pouring over 1,100 rounds of .50 calibre rifle fire into them.”

“When we left, one escort had sunk and the tanker, smoking heavily, was settling fast by the stern, the well deck already awash. Antiaircraft fire from the escorts was intense. It was accurate too. The number 3 engine had been hit. The hydraulic system was severed. And there were holes in the engine nacelles. I was glad when the trip home was over.” For this achievement Lieutenant Commander Muldrow was recently presented with the Distinguished Flying Cross. His crew received Gold Stars in lieu of second Air Medals.

Lieut. Commander Muldrow’s 40 missions in six months in the Marshall and Carolines actions include two low level attacks on enemy shipping in Nusaic harbor—score, two coastal vessels sunk—and several other missions. Most dramatic, perhaps, was a strafing and bombing attack on historic Wake Island – the first daylight, low level strike ever made by heavy bombers.

The following obituary was printed in the Lee County Messenger, Bishopville, SC sometime after May, 1945. It was provided in January 2013 by Jim J. Muldrow of Wilsonville, OR, a first cousin of Lt Comdr John E. Muldrow.

Lt. Comdr. John Muldrow Posthumously Honored

A fifth Air Medal, Purple Heart and Navy Cross has been posthumously awarded to Lieutenant Commander John Ellison Muldrow, whose plane was shot down on May 9, 1945, over Marcus Island.

Cmdr. Muldrow was a native of Bishopville and a graduate of Clemson College and Naval Air School at Pensacola, Fla. He had been in the service for the duration of the war.

After serving as instructor at Jacksonville and Lake City, Fla., he went to the Pacific area as Executive Officer of Squadron VB-108. During this period of service he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and four Air Medals. When his squadron had completed its mission in this area, he was returned to the States to train a new crew at Crow’s Landing, California.

In January 1945 he returned to the Pacific area as Commanding Officer of Squadron VPB-108. A few weeks before his squadron was to return to the United States, he was out over Marcus Island on a mission of vital importance. After completing this task, his plane was shot down while returning to the base of operations. For this accomplishment, he was awarded the Navy Cross.

Besides his mother, Mrs. Annie H. Muldrow, he is survived by his wife, Mrs. Betty Simpson Muldrow, of Fort Worth, Texas.