Richard Thacker Osteen, Jr.

1941

Textile Chemistry

Cadet First Lieutenant, Platoon Leader, Company F, Second Battalion, First Regiment; Phi Psi; Bobbin and Beaker, Assistant Advertising Manager; Greenville County Club; Marksman, ROTC Camp, Fort McClellan, AL.

Greenville, South Carolina

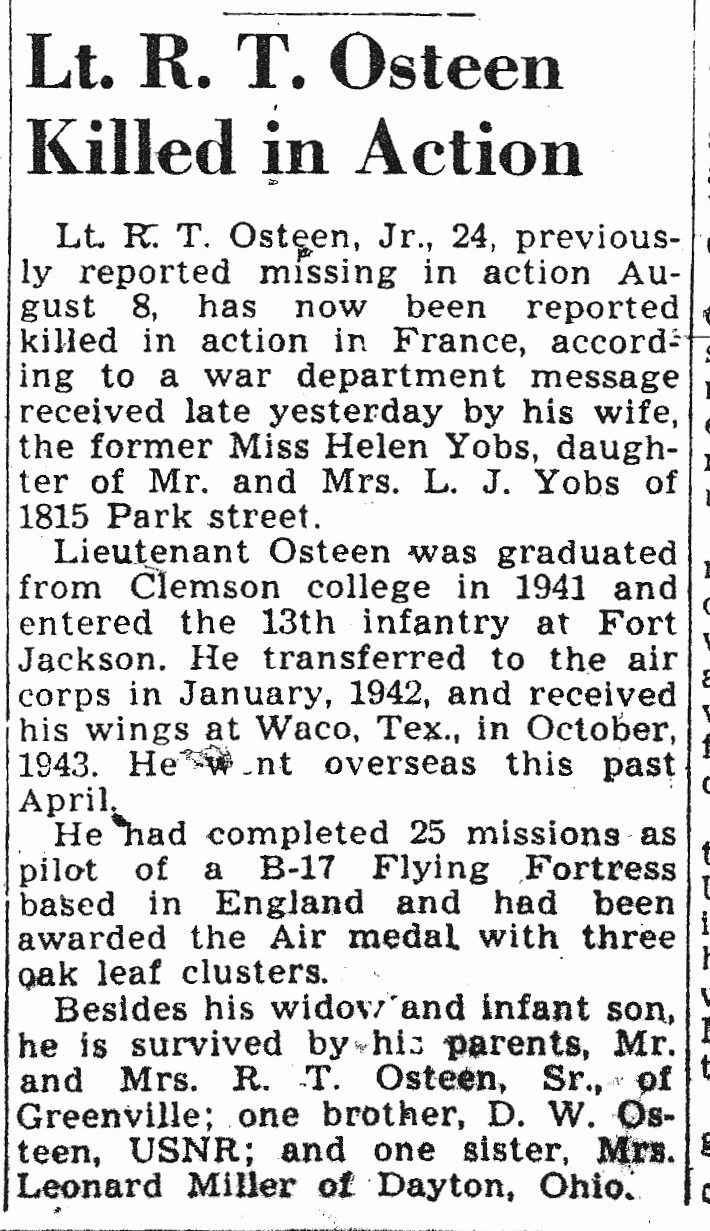

Wife - Helen Yobs and son - Richard T. Osteen, III

Army Air Force, First Lieutenant, B-17

600th Bomb Squadron, 398th Bomb Group

Air Medal with 3 oak leaf clusters.

Apr 12, 1920

Aug 8, 1944

Killed in action during a bombing mission over Caen, France.

Woodlawn Cemetery, Greenville, SC, (S-153-4)

NE

Personal Remembrances

1 Lt. Richard Thacker Osteen, Jr.

April 12, 1920 - August 8, 1944

(with emphasis on USAAF Mission 531, August 8, 1944)

By Frank Bernard Osteen (first-cousin, March 10, 2010)

August 8, 2010, will be the sixty-sixth anniversary of the day that Lt. Richard (Dick) Thacker Osteen, Jr. was killed in action near Pierre-Vieille, or La Chapelle Engerbold, France, some two months after D-Day. These two hamlets are about two-to-three miles apart, and about four-to-five miles north of Conde sur Noireau, a town in Normandy. The 398th Bomb Group’s initial errant bombs fell in the Conde sur Noireau area on August 8, 1944, about 25 miles short of the designated target, a German troop concentration between Cauvicourt and Bretteville le Rabet.

Background

Richard was the son of Richard Thacker Osteen and Clara Emma Barton Osteen, of 11 Perry Road, Greenville, South Carolina. Richard had joined the Sans Souci community’s newly formed Methodist Church at age 13, on May 4, 1933, by profession of faith. He graduated from Parker High School in 1937, and Clemson College in 1941. While at Clemson, Richard was in the ROTC and drilled with the Pershing Rifles. He graduated in 1941 with honors and was commissioned as a 2nd Lt..

Richard immediately entered the Army and within 20 days was in the infantry. In 1943 he transferred into the Air Corps. He earned his wings October 1, 1943, at Waco, Texas. Richard was assigned to the recently formed 398th Bomb Group for B-17 pilot training at Rapid City, South Dakota. The 398th Bomb Group was moved to Nuthampstead, England in April 1944 and became part of the 1st Combat Wing of the 1st Air Division of the “Mighty 8th” Army Air Force. Richard was assigned to the 600th Bomb Squadron. Following three weeks of training and several practice-bombing missions, Lt. Osteen flew his first combat mission on May 6, 1944. It was also the 398th Bomb Group’s first combat mission.

Murphy’s Law

According to Mr. Gordon Alton’s 1st Combat Wing Diary CD, one small error led to a hectic and chaotic introduction to the war for the 398th. The mission was to bomb a German long-range weapons installation in the Sottevast area near Cherbourg, France. The staff duty officer failed to notify the cooks for the early morning mission. The aircrews and ground crews were unfed. The wee-hour briefings were delayed and rushed. The equipment rooms were crowded. The transportation truck broke down, leaving men wandering around in the dark trying to find their planes. Bombs did not get loaded properly. Crews got separated and reconfigured on the spot. Takeoffs were late, as were the assemblies in the air. Some B-17s joined up on whomever they could find. Five B-17s could not find the formation and returned to base. Fortunately the weather over the target was all clouds, preventing any visual bombing. Richard’s aircrew and the other 30 aircrews safely returned to Nuthampstead for some intensive organizational training the remainder of the day.

Col. Frank Hunter, the 398th Commander, got a few things straight with his ground crews and aircrews that very day. It was a good thing, for the next day would be a trip to Berlin, the first of several, on two of which Richard flew. The eight-hour mission went off without a hitch, with all B-17s returning safely. Capt. John M. Baker piloted and Lt. Osteen co-piloted 24 of their 26 missions together. Their combined Mission List is presented separately and not delved into here.

Post-D-Day Setting: Western Front

The Germans were in the process of building launch sites for the “V-1” flying buzz-bomb, which they first used against Paris and London on June 13, 1944. Missions against these long-range weapons installations were dubbed “Crossbow” or “No Ball” missions, “No Ball” apparently referring more specifically to the actual launch sites, once the V-1s became operational. The V-1 “vengeance” weapon wrecked havoc on London and the surrounding countryside to the point that by July, up to one-half of the B-17 missions were to be directed against the numerous launch sites, mostly between 75 and 125 miles from London, within the opposing coastlines of France. The much more sophisticated and feared V-2 rocket became operational in September 1944. The V-2 posed a threat to targets far more distant than London and was much more accurate, flew supersonic to very high altitudes and struck without much, if any, auditory or visual forewarning.

The mission involved the use of the Eighth Air Force’s “Flying Fortress” heavy bombers in support of tactical ground forces’ operations, an experimental battle plan that had shown mixed results over the preceding few weeks. Errant bombs of the low-flying B-24s had killed Allied troops, notably during Operation Cobra on both July 24 and July 25 around St. Lo, which included the death of MG Leslie McNair. Unfortunately, on this Operation Totalize mission, several units bombed errantly due to several factors, mostly 88-millimeter flak.

Eighth Air Force heavy bomber air support was requested and supplied for the Phase II daytime bombing on August 8. The Royal Air Force bombed troop concentrations around Caen the night before in Phase I of the anticipated three-phase operation to take Falaise. Operation Totalize failed to accomplish this ultimate goal and was aborted two days after the Phase II bombing misadventures. It took two more weeks to rout the Germans out of Falaise, which was necessary in order for the allies to proceed on to the Seine and to Paris. Paris was liberated on August 25, 81 days after D-Day!

USAAF Mission 531

Richard’s combat tour was extended due to the intensity of the air war over Europe following D-Day. To put things into context that day, Richard’s B-17 was one of 37 B-17s out of Nuthampstead, of a total force of 681 B-17s and 100 P-51s from numerous bases scattered about England for the mission. They were “dispatched to bomb enemy troop concentrations and strong points south of Caen,” which is in Normandy, France. This low-level mission was in support of Operation Totalize, a First Canadian Army endeavor to break out of Caen and push the Germans out of Normandy by way of Falaise, a city 18 miles to the south-southeast. The B-17s normally bombed from 26,000 feet or higher; these low-level missions were flown from 10,000 to 15,000 feet, subjecting the B-17s to encounter much more accurate and intense ground fire.

The 1st Air Division’s 379th and 401st Bomb Groups accidentally killed numerous Canadian, Polish and British troops and destroyed much Allied equipment immediately around Caen, a stubborn German stronghold in the Canadian sector of operations in Normandy. Each of these Bomb Groups lost a B-17 without a subsequent MACR (Missing Air Crew Report), the 379th over the target area and the 401st over Caen.

Due to flak damage shortly after beginning the bomb run some 10-15 miles south of the designated Initial Point (IP), the 398th Lead B-17 (Wagner/Hopkins) trained its bombs moments after being hit and moments before crashing, prompting the Lead and Low Squadrons to do likewise, bombing some 25 miles short of the designated target. Within one-to-four minutes, a Low Squadron B-17 (Blackwell/Anderson) and a High Squadron B-17 (Baker/Osteen) were shot down. All three B-17s were hit within eight-to-ten miles of each other, about 20-to-25 miles southwest of the target. All 398th bombs fell some 10-to-25 miles short of the designated target, upon both friend and foe. Three other Bomb Groups, the 100th, 91st and 306th, each sustained a MACR B-17 loss within the same eight-to-ten mile diameter circle, centered approximately one mile west of Proussy.

Richard, recently married and an expectant father, was co-piloting a B-17G on his 26th combat mission, when 88-millimeter flak shot down his B-17 from around 14,000 feet at around 1302 hours (MACR time 1259 hours) over the Pierre-Vieille area, France, on August 8, 1944. Shortly after flak hit the left wing per three witnesses, or right wing per one witness, the wing folded back and the B-17 went into a deep spiral to spin, affording little time or circumstance for escape. Tech. Sgt. Jerome Fields, parachuting to safety through the open bomb bay, last saw Richard trying to don his parachute as the crippled bomber headed for the earth. G-loads prevented Richard’s escape. According to witnesses, his B-17 had not dropped its bombs before it was hit. A post-war letter of Tech. Sgt. Fields suggested that the bombs were salvoed before he and Lt. Selby Hereid bailed out through the bomb bay. Several of those airmen involved have described the August 8, 1944, low-level mission as one of the most terrifying flak encounters of their World War II missions.

Aftermath

So, for the 398th Bomb Group, the mission was harrowing, became somewhat chaotic, was counter-productive and very costly in terms of lost aircraft and lost lives, both in the air and on the ground. Eighty-eight millimeter flak damage definitely contributed to the misadventures of errant bombing that day and to the losses of the 398th Bomb Wing.

The mission losses included three P-51s and seven B-17s overall (actually eight); another 298 B-17s were damaged, four beyond repair. Of these losses, the 398th Bomb Group lost three B-17s. Two of the pilots of the other two 398th B-17s that German flak shot down that day survived the war. Meyer “Buddy” Wagner, wrote the 2003 book, Flying Blind, which detailed his survival experiences, and Wallace “Wally” Blackwell, was past-President of 398th Bomb Group Memorial Association, who died January 14, 2009. The 398th Lead pilot and navigator, Capt. Meyer Wagner and Lt. Vonnerlin Wernecke, escaped the Germans in Paris and were repatriated on August 26, the day of the Paris liberation parade. (Flying Blind, M. C. “Buddy” Wagner, Jr.)

Although Lead’s pilots, Capt. Meyer Wagner and Capt. Robert Hopkins, both sustained shrapnel wounds, Capt. Wagner managed to fly for several minutes to allow his crew to bail out, before bailing out himself to live an adventuresome cat and mouse life for eighteen days evading the Germans in Paris, along with Lt. Vonnerlin Wernecke. Six other survivors became and remained POWs. Lead’s Ball Turret Gunner, SSgt. James F. Hochadel, was killed while in his parachute and was buried where he landed. The Bombardier, Lt. Charles Arnold, also was probably killed prior to hitting the ground. Ten chutes were seen; several surviving POWs stated that they were fired upon in the air by German ground troops.

2nd Lt. Blackwell’s aircraft tail was shot off, killing the tail gunner, Sgt. Charles Simons. Despite the damage, Lt. Blackwell and 2nd Lt. Roy Anderson managed to overfly the formation and fly to the northwest to friendly territory for several minutes before the remaining eight airmen could bail out, all to be returned to duty. The aircraft wreckage was found around 22 miles to the NNW of where Blackwell’s crew successfully bailed out.

Although Capt. Wagner later (16 Nov 1944) deservedly received the Silver Star for his heroic efforts during the shoot-downs while wounded, 2nd Lt. Blackwell’s skillful flying and perseverance (and a little more luck) enabled the remaining eight airmen of his tail-less aircraft to survive, and not be captured. I found no Distinguished Flying Crosses (DFCs) listed in the 398th’s records for this 8 August 1944 mission! Lt. Blackwell was the 398th’s unsung hero of the otherwise disastrous mid-day 88-mm. encounters somewhere between Vire and Cauvicourt, France. Having reviewed pertinent records from numerous sources, I firmly believe that Lt. Blackwell’s flying and decision-making prowess on 8 August 1944 warranted the Bronze Star, if not at least the Distinguished Flying Cross, or other air medal.

Of Richard’s nine-man crew, he and six others were killed. Under German guard, TSgt. Jerome Fields and Lt. Selby Hereid buried the dead, before becoming interned themselves as Prisoners of War. Those killed were Capt. John Baker, 1st Lt. Richard Osteen 1st Lt. John Kressenberg, TSgt. Roy A. Johnson, SSgt. Leonard D. Harrison, SSgt. Michael A. Romano and SSgt. William H. Wilson. Hopefully, there are other surviving airmen of these three aircrews. Of the three downed 398th B-17s’ airmen, ten airmen were killed, ten were taken POW (Wagner and Wernecke escaped) and eight of Blackwell’s crew parachuted into friendly territory and were returned to duty. Richard’s remains were moved from the US Forces Cemetery at Marigny, France, and re-interred at Greenville’s Woodlawn Memorial Park in January 1949.

Dangerous Missions

Reviews of the family’s hand-written mission list and of 398th Bomb Group and 1st Combat Wing CD records reveal the following observations. Only 26 missions could be confirmed:

Richard’s first combat mission was on May 6, 1944. By June 19, Richard had flown five of the twelve missions to date in aircraft # -7218. That B-17 was flying as Richard’s left wingman on the July 7 mission to Leipzig when it got shot down, along with another 398th B-17. The very next day, July 8, B-17 # -7096 was shot down on a mission to Humieres-Fresnoy, a B-17 Richard had flown on his third mission to St. Dizier on May 9. It was one of three Lead element aircraft, along with Richard’s wingman, that flak removed from battle that day. Then, on the August 6 mission to Brandenburg, B-17 # -2467 got shot down; Richard had flown that B-17 on the June 2 Boulogne mission. Finally, on August 8, Richard co-piloted B-17 # –7399, his fifth occasion in that aircraft since his seventh mission to Ludwigschafen on May 27.

Thus, Richard flew 12 of his 26 missions in the above four B-17s that were lost between May 6 and August 8, 1944. Prior to Richard’s loss on August 8, besides the knowledge of the fates of the three previously flown B-17s, Richard’s 26 missions were witness to some 16 losses of 398th aircraft, occurring in nine of those missions.

Surely, the proximity of death that had played out numerous times within three months of combat must have weighed heavily on the minds and hearts of Capt. Baker, Lt. Osteen and the other eight crewmembers. An interesting finding was the recent discovery of the existence of a 398th Bomb Group Memorial Association photo of Capt. John M. Baker and Lt. Richard T. Osteen, taken on August 7, 1944, one day before their deaths. Lt. George Schatz, 600th BS, had submitted the photo.

398th Bomb Group records reveal the following facts: The 398th’s B-17 loss rate for Richard’s 26 missions was 0.65 losses/mission; that of the 398th’s total of 64 missions flown by August 8 was 0.34 losses/mission; and that of the other 38 missions flown (64-26) by August 8 was 0.13 losses/mission. From April 22, 1944, to May 26, 1945, the 398th Bomb Group lost 58 B-17s on 195 combat missions, for an overall loss rate of 0.30 B-17 losses per mission.

To extrapolate, Lt. Osteen’s 26 missions were twice as dangerous, with reference to the chances of being shot down, than the average of all of the 398th missions flown and were five times as dangerous as the average of the other 38 398th missions not flown by the Baker/Osteen crew through August 8, 1944. One obituary stated that Lt. Osteen had been awarded the Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters. Some 398th missions records and awards records are illegible. These records may be pertinent to Lt. Osteen and may contradict certain observations as written.

Pilot’s Wings Insignia

Richard’s family and friends have revealed the story of the Sans Souci community’s beloved and belated public servant, Judge Frank Eppes, shortly before the fateful 1944 flight. Frank had finished Parker High in 1941; he was an aircraft mechanic stationed in England and was visited by Richard a few days earlier. The story is told that Richard took off his pilot’s wings insignia and gave it to Frank to deliver to his (Richard’s) child (unborn son) upon Frank’s return home. Even though Frank is said to have mentioned that the mission was (possibly) to be Richard’s last required mission, Richard apparently expressed to Frank that he probably would not be coming back. He didn’t. Richard T. Osteen, III, was born in Columbia, SC, on October 19, 1944.

Richard’s August 5, 1944, letter to his mother stated that he had visited Frank Eppes (at Frank’s base) on August 3. He further noted,

“Of course, the last missions seem to come much slower than the first ones. I know that I’ve been “sweating out” the last few that I’ve been on.”

A March 17, 2010, the Upstate's The Times Examiner article By Frank Bernard Osteen (first-cousin)

Additional Information

“Capt. John M. Baker pilot and Lt. Osteen co-pilot”

Eye Witness Description of Missing Aircraft B17G 42-97399, MACR #7383 Pilot, Captain John M. Baker, 0-24753, 600th Bomb Squadron, 398th Bomb Group on Combat Mission to Bretteville le Rabet, France 08 August 1944.

Captain Baker was flying as deputy lead in the high group. We (Lt Elwood’s crew) were flying just above and to the right of his ship, leading the high squadron of the high group. A burst of flak hit close to Captain Baker’s number three engine in the wing causing sudden heavy fire, resulting in the almost immediate loss of that right wing, and the ship went into a spin. I saw him spin over three or four times in about ten seconds.

This occurred during the bomb run wherein I was acting as bombardier. My pilot, Lt Elwood, also observed the incident and on alerting the crew to watch the plane we did not see any parachutes while the plane was visible from our position. It is not impossible that parachutes could have been observed by planes to our rear.

s/GEORGE E SCHATZ, 0-757043

2nd Lt, Air Corps

Bombardier, B17G